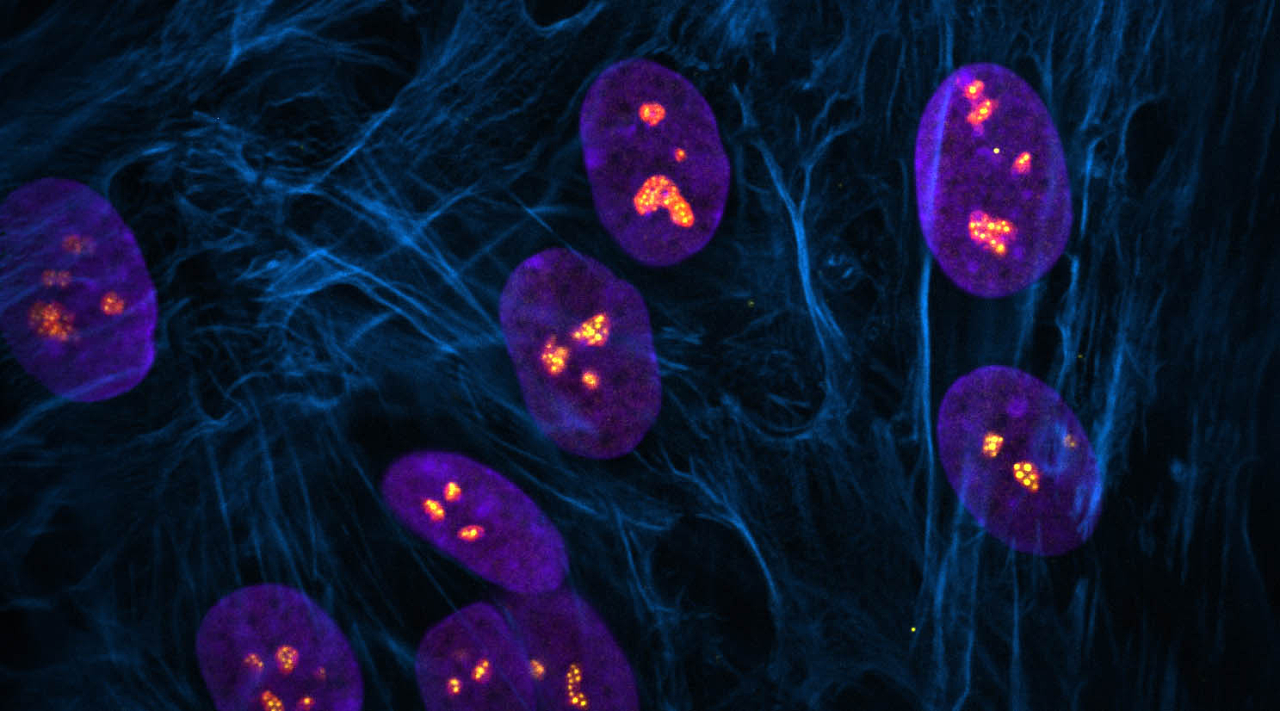

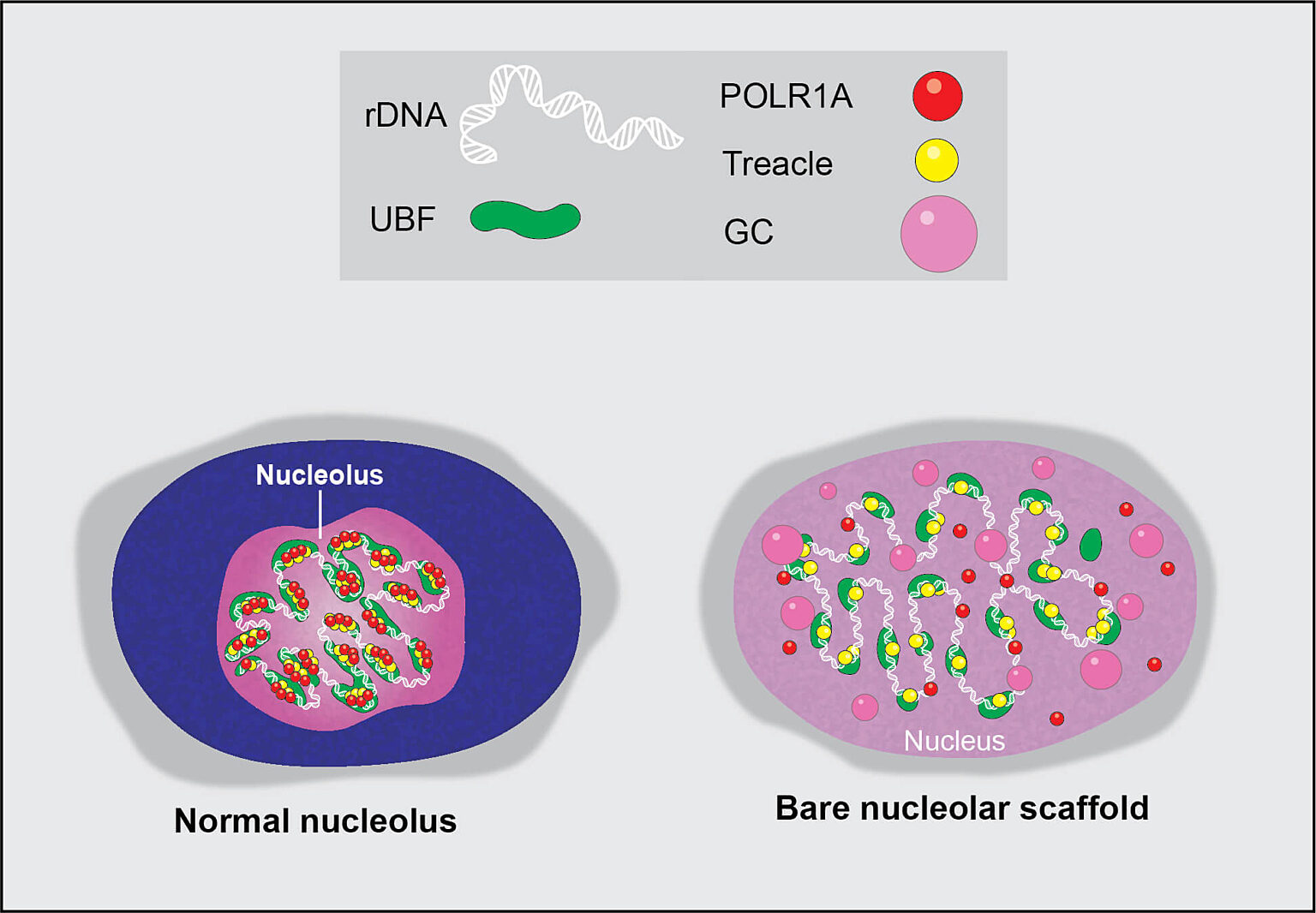

The nucleolus is a special part of the cell nucleus that houses ribosomal DNA, and where ribosomal RNA production and ribosome assembly largely takes place. Nucleoli can vary greatly in appearance, serving as visual indicators of the overall health of this process. Thus, the team found a way to capitalize on this variation and asked how chemotherapy drugs impact the nucleolus, causing nucleolar stress.

“In this study, we not only evaluated how anti-cancer drugs alter the appearance of nucleoli, but also identified categories of drugs that cause distinct nucleolar shapes,” said Gerton. “This enabled us to create a classification system for nucleoli based on their appearance that is a resource other researchers can use.”

Because cancer’s hallmark is unchecked proliferation, most existing chemotherapeutic agents are designed to slow this down. “The logic was to see whether these drugs, intentionally or unintentionally, are affecting ribosome biogenesis and to what degree,” said Potapova. “Hitting ribosome biogenesis could be a double-edged sword—it would impair the viability of cancer cells while simultaneously altering protein production in normal cells.”

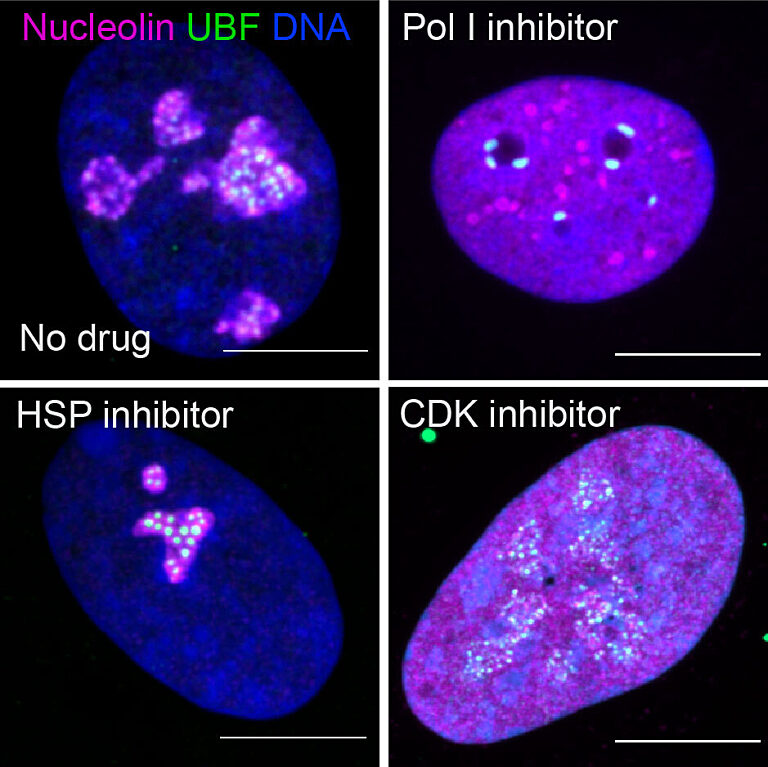

Different drugs impact different pathways involved in cancer growth. Those that influence ribosome production can induce distinct states of nucleolar stress that manifest in easily seen morphological changes. However, nucleolar stress can be difficult to measure.

“This was one of the issues that impeded this field,” said Potapova. “Cells can have different numbers of nucleoli with different sizes and shapes, and it has been challenging to find a single parameter that can fully describe a “normal” nucleolus. Developing this tool, that we termed “nucleolar normality score,” allowed us to measure nucleolar stress precisely, and it can be used by other labs to measure nucleolar stress in their experimental models.”

Through the comprehensive screening of anti-cancer compounds on nucleolar stress, the team identified one class of enzymes in particular, cyclin-dependent kinases, whose inhibition destroys the nucleolus almost completely. Many of these inhibitors failed in clinical trials, and their detrimental impact on the nucleolus was not fully appreciated previously.

Drugs often fail in clinical trials due to excessive and unintended toxicity that can be caused by their off-target effects. This means that a molecule designed to target one pathway may also be impacting a different pathway or inhibiting an enzyme required for cellular function. In this study, the team found an effect on an entire organelle.

“I hope at a minimum this study increases awareness that some anti-cancer drugs can cause unintended disruption of the nucleolus, which can be very prominent,” said Potapova. “This possibility should be considered during new drug development.”

Additional authors include Jay Unruh, Ph.D., Juliana Conkright-Fincham, Ph.D., Charles A. S. Banks, Ph.D., Laurence Florens, Ph.D., and David Schneider, Ph.D.

This work was funded by institutional support from the Stowers Institute for Medical Research.

About the Stowers Institute for Medical Research

Founded in 1994 through the generosity of Jim Stowers, founder of American Century Investments, and his wife, Virginia, the Stowers Institute for Medical Research is a non-profit, biomedical research organization with a focus on foundational research. Its mission is to expand our understanding of the secrets of life and improve life’s quality through innovative approaches to the causes, treatment, and prevention of diseases.

The Institute consists of 20 independent research programs. Of the approximately 500 members, over 370 are scientific staff that include principal investigators, technology center directors, postdoctoral scientists, graduate students, and technical support staff. Learn more about the Institute at www.stowers.org and about its graduate program at www.stowers.org/gradschool.

Media Contact:

Joe Chiodo, Head of Media Relations

742.462.8529

press@stowers.org