News

09 October 2025

2025 Lab Coat Ceremony Welcomes Graduate Students To Their Thesis Labs

An annual tradition marks the start of scientific discovery for the 2024-2025 class of Stowers Graduate School students.

Read Article

News

The sea lamprey is a valuable research organism for exploring evolution

By Rachel Scanza, Ph.D.

In the dark depths of the ocean, a monstrous-looking sea creature lurks in the murky deep, as fascinating as it is fearsome. The sea lamprey, with its many menacing teeth, is hunting for its next meal. Suddenly, a fat and fleshy fish swimming nearby finds the lamprey’s mouth suction-cupped to its side, chomping its flesh and draining its blood.

The sea lamprey, or Petromyzon marinus, is often referred to as a “vampire fish.” With origins tracing back 500 million years, these eel-like animals are ancient vertebrates with a striking appearance. Notably lacking a jaw, the sea lamprey mouth is larger than its head and filled with circular rows of razor-sharp teeth decreasing in circumference down to its toothed tongue.

For scientists, the sea lamprey may hold keys for unraveling how animals’ complexity and diversity have evolved, offering a powerful system through which to study our own evolution and potentially leading to better understanding health and disease.

Why do scientists study sea lampreys?

Sea lampreys sit at the base of the vertebrate tree of life. Their biology may help scientists understand animals higher up this tree, including humans, giving us insights into the evolution of development, the nervous system, and the immune system.

Striking images of the sea lamprey and its many menacing teeth.

One remarkable feature of the sea lamprey is its ability to regenerate its spinal cord, something humans certainly cannot do. Another curious characteristic was discovered after sequencing the sea lamprey genome in 2013. During development, lampreys lose 20% of their DNA—and they do so on purpose. This programmed loss and rearrangement of chromosomes remains an active area of investigation.

Notably, fossil records dating back more than 300 million years suggest that the sea lamprey form and function have remained virtually unchanged. These resilient and predatory sea creatures survived four mass extinction events, including the meteor impact 66 million years ago that wiped out the dinosaurs and more than 80% of life on Earth. Thus, understanding their resilience even through apocalypses may be invaluable for ensuring our own survival.

Sea lamprey research at the Stowers Institute

Researchers at the Stowers Institute, including Investigators Robb Krumlauf, Ph.D., and Tatjana Sauka-Spengler, Ph.D., study sea lamprey genetics linked to development. Although sea lampreys are not housed in Kansas City, they are part of our “unordinary organism” arsenal thanks to collaboration with the lab of Marianne Bronner, Ph.D., at the California Institute of Technology, who oversees one of the premier lamprey facilities in the world.

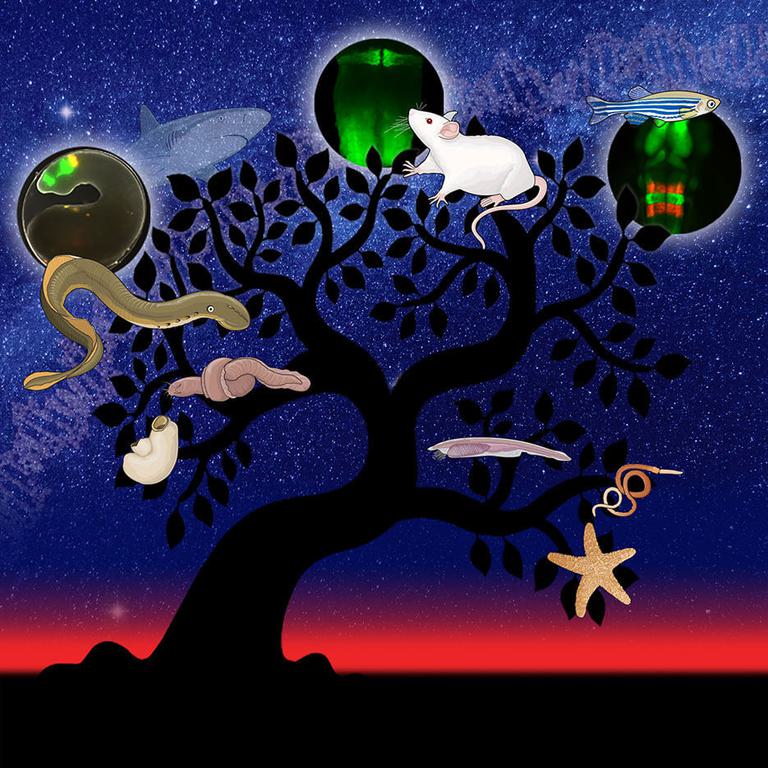

Graphical illustration of an evolutionary "tree of life." The sea lamprey, while occupying a different branch than more advanced vertebrates like a mouse or zebrafish, uses a similar genetic toolkit during development.

For Krumlauf, the sea lamprey evokes a fundamental question: How did the brain evolve? The Krumlauf Lab has identified that the same genes are involved in guiding not only head-to-tail body patterning but also in building the hindbrain—the brain region controlling vital functions like blood pressure and heart rate—for both humans and sea lampreys. And both the Krumlauf and Sauka-Spengler Labs are seeking to identify first principles, or rules guiding how conserved vertebrate traits arise, like the hindbrain, in their jawless vertebrate counterparts.

Genes do not act autonomously. Rather, genes are part of interconnected networks or circuits where they interact with regulatory elements and molecular signals, turning on and off at the appropriate times to inform cell fate. Studying sea lampreys is essentially like taking a time machine into the distant past to gain insight into the circuitry we share with these ancient ancestors, and it may help us identify short circuits underlying disease.

Sea lamprey’s great invasion of the Great Lakes

Carnivorous and predatory, in the 20th century, sea lamprey’s list of attributes expanded to include “parasitic” when these Atlantic Ocean-dwelling creatures migrated inland. Manmade channels and canals allowed them to colonize, and catastrophically demolish fish populations in the Great Lakes.

Their invasion, amplified by an abundance of prey and a lack of predators, was devastating to fisheries and water recreation—so much so that multiple government initiatives were deployed to combat the crisis. Collaboratively, the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Canadian government, and research partnerships established methods to control sea lamprey parasites.

Biologists even developed a lamprey-specific pesticide called a lampricide. Along with traps, nets, and careful monitoring efforts, it reduced sea lamprey populations in the Great Lakes by 90%. This successful collaboration has largely restored the swimming conditions enjoyed by fish and people alike.

However inconvenient the sea lamprey can be, they are valuable for exploring evolution.

“We have this picture of the ugly face of a sea lamprey and next to a mouse or a human, it is hard to imagine they are related,” Krumlauf said. “Yet basic parts of their brains and heads are formed in exactly the same way as ours.”

News

09 October 2025

An annual tradition marks the start of scientific discovery for the 2024-2025 class of Stowers Graduate School students.

Read Article

News

12 February 2025

The Sauka-Spengler Lab explores the blueprint and circuitry driving cells

Read Article

News

01 November 2024

Organized by Stowers Institute Investigators Matt Gibson, Ph.D., Tatjana Sauka-Spengler, Ph.D., and Robb Krumlauf, Ph.D., the conference facilitated a collaborative environment aimed at creative scientific exchange. More than 100 participants attended, including 20 distinguished speakers and trainees.

Read Article